With the hunting season drawing to a close, my opportunities to fill my freezer were dwindling. However, Mother Nature showed me some pity and I was able to harvest a healthy doe before the season ended. I had never processed a deer from kill to freezer, but this year was as good as any to give it a try. I had three reasons for wanting to process my own deer.

Disclosure: Adam’s Garden of Eatin’ participates in affiliate marketing programs. There are some affiliate links below and I may receive commissions for purchases made through links in this post, but these are all products I highly recommend. I won’t put anything on this page that I haven’t verified and/or personally used.

The first reason was I just wanted the knowledge of experience. Learn by doing. The more I did, the more satisfaction I gained. When I was finished, I had this incredible sense of self-accomplishment. It’s a concept that’s foreign to most people today thanks to easy convenience.

The second reason for processing my own deer is the lack of space. I’ve been seeing reports of processors having to turn people away because their freezers are already maxed out. I didn’t want to fight for freezer space at an already over-crowded deer processor this season. COVID has given people a lot of extra time on their hands this hunting season and that’s been evident at the processors. “That guy” finally decided to get up off the couch and finally give hunting a try. Now processors are full of deer inventory. That’s a great thing for the sport of hunting, but a little annoying when I can’t get a deer processed in a timely manner.

The third reason is really just my own personal hang-up. You may have a personal relationship with your butcher and 100% trust in their work. I am not that fortunate. It’s hard to have 100% trust in what you’re getting from the processor is really YOUR deer. How cleanly was your deer handled? It might have been hung next to a nasty gut-shot deer from the other guy, but you wouldn’t know it. Ya know, trust issues. Processing my own leaves nobody to blame but myself if something goes sour.

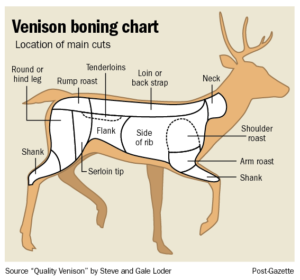

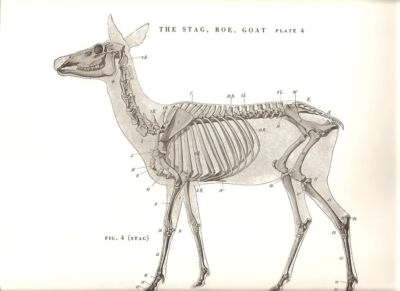

So I started with a cleaned and skinned carcass, ready to butcher. The field dressing and skinning steps are a tad graphic, so they’ll be for another post. Butchering my own deer wasn’t as complex as I had anticipated. The majority of wild game animals have the same similar body structure. I have butchered hogs before, so the anatomy wasn’t all that different. However, I did first watch the Bearded Butchers YouTube video on how to butcher a deer. I found it was very thorough and that gave me some good pointers before I cut anything.

Some hunters prefer to age their meat to enhance flavors. Aging creates unique flavors that you just can’t create unless given the time. Different amounts of time develop different flavors.

Most meat agers have one or two things going for them that I don’t. Some just have a straight-up walk-in cooler. Nothing to worry about. Just hang out and come back later. Well, I don’t have a walk-in cooler in my garage, so that wasn’t an option. Others are just blessed with the right climate. Cold winter days and nights are perfect conditions for outside hanging. Temperatures stay steadily cold, so the risk of meat spoilage is low. I would have loved to let my meat age, but I’m a realist. I live in Tennessee where winter temps are temperamental.

We fluctuate from low teens to upper 60s over the course of a day, so hanging a deer outside for a week, wasn’t really an option.

I just let my deer hang overnight and then butchered it the next day. The overnight hang allowed for any remaining blood to drain and firmed up the meat. The firming up of the meat made for easier slicing and grinding throughout the process. COLD is your friend when deer processing.

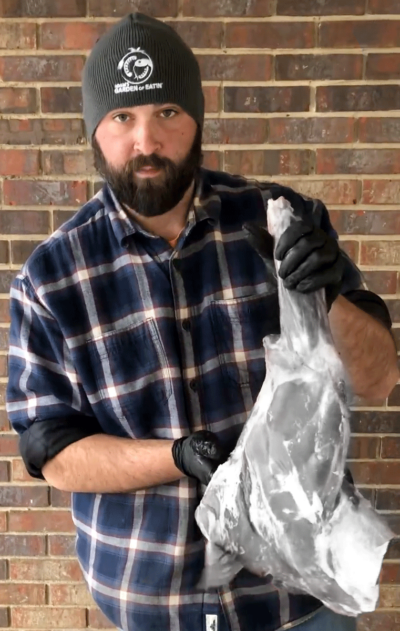

Step 1 – Set Up

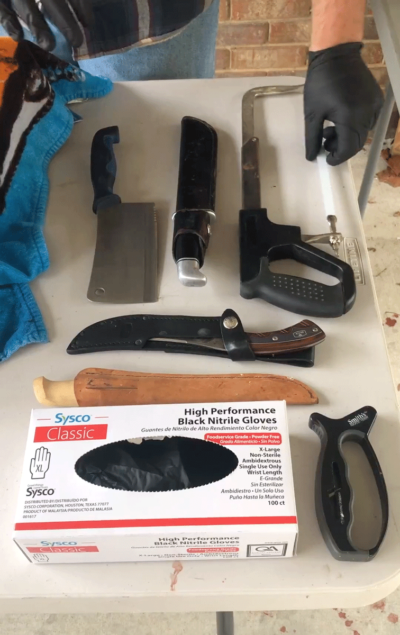

- Prepare thy work station. A clean organized workstation, with all my tools laid out, made the process go a lot easier. I used a plastic folding camping table I had in my garage as my butchering table. Cleaned and sanitized of course.

- GLOVES. Gloves are crucial for keeping cross-contamination in check. Tainted venison meat can lead to spoilage and “off” flavors.

- Knives. I used three knives in total. I used my Buck general 120 for the large forceful cuts. My Buck Open Season Boning knife for the majority of the butchering. And my Rapala fillet knife for filleting silver-skin and membrane.

- Sharpen thy knives. A sharp knife is safer than a dull one because less force is used when making cuts. Less force means less chance of a nasty blade slip into your finger. I used my Smith handheld sharpener because it was fast and effective.

- A Saw. A deer can be processed with nothing more than a single knife, but I found the saw just made for easier work on some of the bones. Separating the hindquarters and ribs would have been much harder without it.

- Vacuum Sealer. I highly recommend investing in a vacuum sealer of some kind if you are trying to process your own venison. You can use freezer paper and tape, but I find the vacuum seal bags eliminates any air from getting to your meat in the freezer. Air access is what can cause freezer burn. The vacuum seal bags will extend the freezer life of your meat.

- Grinder. I prefer the majority of my deer to be processed into a coarse grind. It is possible to create ground venison with a sharp knife, but it’s going to take a while, so I recommend investing in a meat grinder. It made the grinding step so much faster and easier.

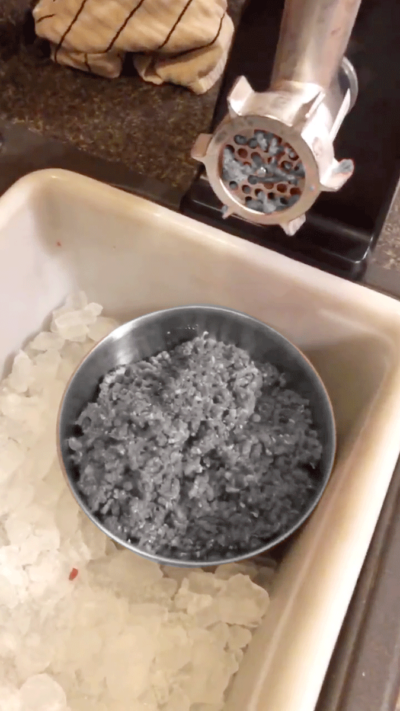

- Cold Bowls. All my metal bowls spent a few hours in the freezer before being used. I used my biggest bowl as my grind pile. This is the pile of all my meat scraps destined to be run through my grinder.

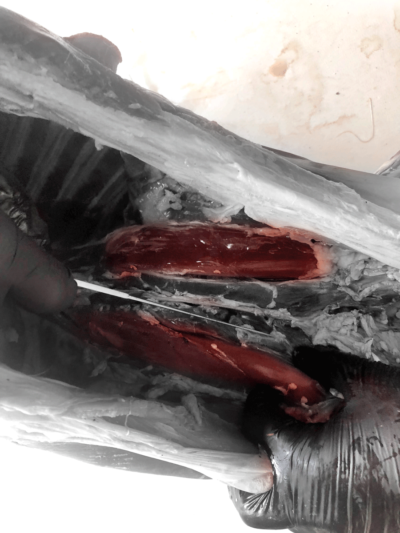

Step 2 – Tenderloins

The true tenders are two pieces of meat that run along the inside spine of the deer. These are the best cuts from the entire deer and easily removed with a few slices of a knife. Some hunters forget to save these out when butchering because they’re somewhat hidden and can be forgotten about. That’s a shame because they are so delicious. That was the first piece of meat I collected. Whenever possible, I like to eat my tenderloins fresh from harvest.

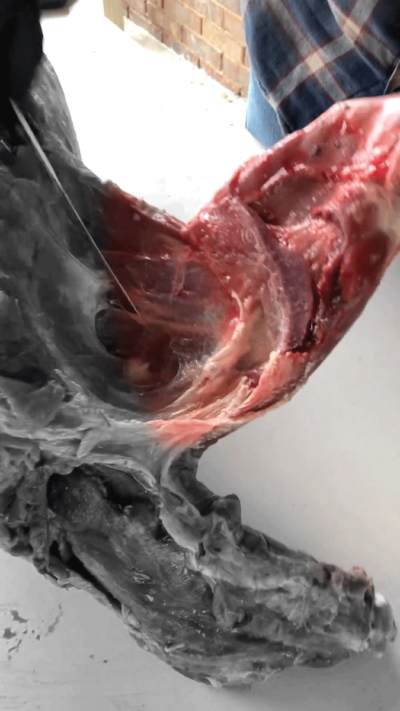

Step 3 – Hind Quarters

The hindquarters are easier to process if removed from the actual body. This is where the saw came I handy. I just sliced through the meat until I hit the bone and then sawed through the spine until separated. One tip I did read, was in regards to using a knife and a saw. Don’t start sawing through the muscle until you’re actually at the bone. Sawing meat can make a nasty mess, so always slice through the meat with your knife first, until you reach bone. Then switch over to the saw to cut through the spine. Then finish it off with your knife again. You’re only needing the saw to cut through the bone. Not the muscle. Cut muscle with a knife and bone with a saw.

Once separated from the body, I split the hindquarters in half. I ran my knife down the middle until I hit the hip socket. I added some downward pressure and it popped it out of the socket. I then just cut the rest of the leg away. I’m sure a professional butcher would get a cleaner cut than what I made, but I was wanting a few pieces for some roasts and the rest was going in the grind pile, so the presentation wasn’t a high priority.

Step 4 – Front Shoulders

The front shoulder removal is pretty straightforward. I ran my knife down through the armpit while I pulled back on the leg. It separated very easily. The removal could have been done a tad cleaner, but the front shoulders were going to grind pile anyway, so it didn’t matter to me.

Step 5 – Backstrap

The backstraps are the most prized pieces of the whole deer. They are the muscles that run along the back of the deer next to the spinal column. Hence the name. They were very easy to remove.

I began slicing down the length of the muscle. I kept my cut parallel and used the spinal column as a guide. I slowly peeled and worked the muscle off of the bone. Flip the deer over and do the same for the backstrap on the reverse side. You should be left with two prized pieces of venison meat ready for further processing.

Step 6 – Ribs

Saving the ribs from a deer is the hunter’s choice. There really wasn’t enough meat left on the ribs to warrant saving, but I harvested them for learning purposes anyway. I took my saw and went right down next to the spine. I felt each rib cut through as I sawed. I started cutting with my hand saw and it was taking a little more effort than I wanted. So I broke out the saw-zaw and finished the job. Wear your safety glass when using power tools.

One of the ribs had a massive hole in the side from the bullet wound. I knicked the stomach slightly with my shot, so some of the nastiness had stained the meat around the wound. Stomach contents can ruin deer meat, so I just cut all the nastiness away. You can attempt to clean the opening with water and save the meat, but I didn’t want to risk it. So I just cut it away.

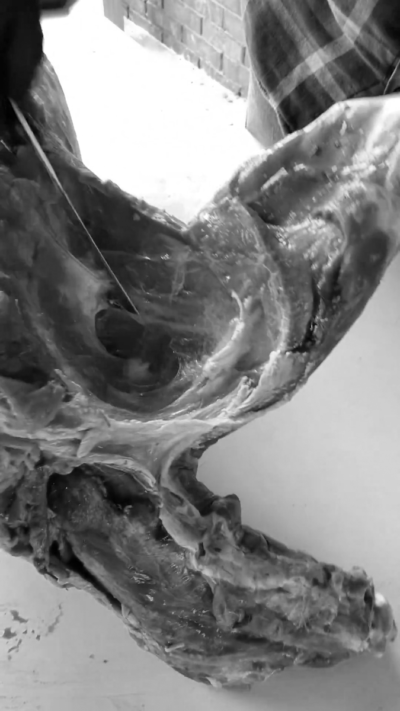

Step 7 – The Neck

The neck meat on a deer can be tough, so it makes for great stew meat. Or just add it to the grind pile as I did. I needed to remove the neck bone, so I just worked my knife along the bone until I cut off all the chunks of meat.

The presentation wasn’t a priority here either because everything would go in my grind pile. I’m sure someone who knows what they’re doing could cut a pretty cut off of the neck, but I’m a novice.

Step 8 – Bone It.

The bone in the rear leg was pretty easy to remove. It’s a straight bone that can be easily carved around with a knife. I used the seam butchering technique. This is when you follow the lines of the muscles with your knife. Muscle groups are laid on top of one another, so they are fairly easy to discern. Some of the bigger pieces just peeled away without even using my knife. I put aside the prettiest cuts that would be saved roasts and put the rest in my grind pile.

The front shoulders can be a little trickier because you have to work around a joint and shoulder blade. First I made a cut at the joint and separated the front shanks. Then I proceeded to cut out the shoulder blade. Shoulder meat is good for stew, burgers, jerky, etc. The final results weren’t pretty but it was all going in my grind pile anyway. I then took the shanks and cut away any extra meat as well.

Step 9 – Trim It.

Now that I had my deer fully boned out, I proceeded to the final trimmings. This is where I went super detailed with the knife. Silverkin and membrane can make for a bad eating experience. It’s tough, chewy, and pulling a piece of sinew out of your teeth while you eat can make a person cringe. I took my time and thoroughly removed all silverskin membrane and fat. I went as thoroughly as I could. I didn’t want any fat left because wild game fat can cause gamey flavors in your meat. I probably went a little too thorough with removing the membrane though. Some of the thin membranes will render out when cooking, but I didn’t want to take any chances. I cut everything off I could. This is where you can make or break your final results.

Step 10 – Grind It.

Once I had all my cuts trimmed and clean, it was time for the grinding. This is where all the scraps, bits, and pieces from the whole process were used. I placed all my bowls and attachments in the freezer to chill overnight. Once again, COLD is your BFF when grinding meat. I cut all the bigger chunks into 1-2” pieces and trimmed out the excessively large pieces of fat and sinew.

I didn’t go as thorough with the trimming on the scrap pile because I wanted to see how well my grinder handled fat and sinew. It worked flawlessly. It ate through everything I fed it and did it in super-fast time. I had planned on running everything through the grinder twice, but I was so pleased with the texture of the first grind, I decided to leave it alone.

When grinding venison or any type of meat, it’s recommended to partially freeze your meat. It cuts down on the smearing in the grinding gears. You want your meat to grind, not smear. I placed a chilled bowl placed inside a container of ice as my grind collecting vessel. It kept the bowl and meat super cold while I worked. After everything was run through the grinder, I portioned the grind out in my vacuum seal bags. Portion size is totally at your discretion. I was running out of gas towards the end, so my portions were “fill the bag, seal the bag”. I scribbled the date and contents on the bag and put them in my game freezer for future uses.

4 Lessons Learned

So here are some lessons I learned from processing my own deer for the first time.

Lesson #1

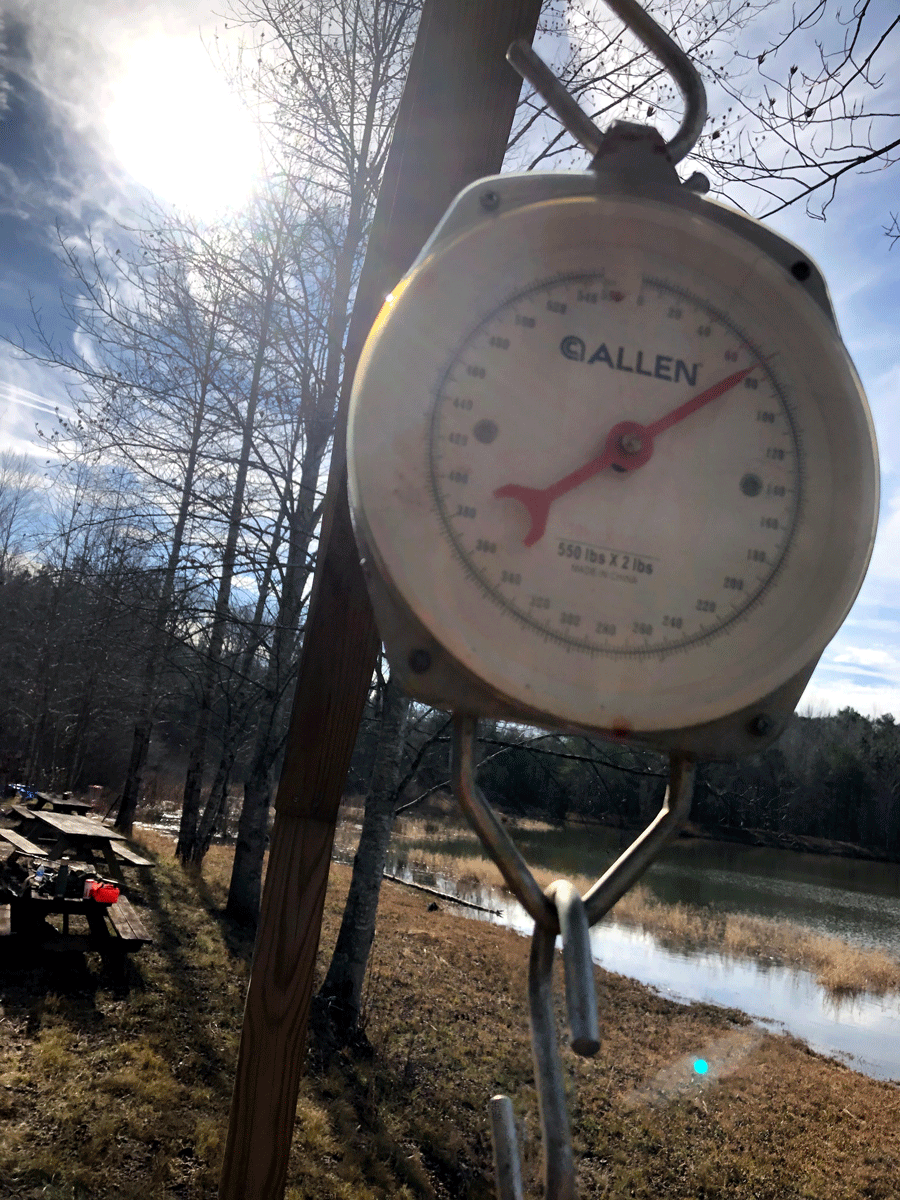

Time equates to speed. It would be considered criminal how long it took me to process my one doe. 7 hours from start to freezer. That’s comical by some hunter’s standards, but I was trying to document my amateur butcher experience at the same time.

Lesson #2

Satisfaction can’t be replicated.

Full processing took me waaaay longer than I thought it was going to take, But the satisfaction I got from harvesting and processing my own game couldn’t be replicated any other way. Making one or two perfect cuts while butchering is just one of those small satisfactions I experienced.

Lesson #3

A renewed respect for the game processor.

I have always had respect for the wild game processors out there, but this process just reaffirmed it. It took me all day to process my one deer. The fact that some of these guys can quarter 3 deer in an hour is astounding. And by the end of the day that $60 processing fee was looking mighty cheap.

Lesson #4

Money equals time.

The more money you’re willing to invest, the faster the process can go. I didn’t go overboard, but I invested in some equipment before I ever started processing. Plus I would have equipment for my next deer.

Yes, you can process a whole deer with just a knife. Frontiersmen did it that way for hundreds of years. But it might take some time. A power saw makes for super quick work when cutting through bone.

Yes, you can make your own ground venison with just a knife. But it might take some time. A grinder flew through my meat cuts in record time with no fuss.

Yes, you can wrap your cuts in freezer paper, tape them up and label them. But it’s going to take more time if you don’t have a vacuum sealer. Stuffing pre-cut bags, closing the lid, and pushing a button, was way easier than wrapping everything individually.

All in all, I have replenished my game freezer for the next year. I have my ground venison, my roasts, and my backstraps ready to be cooked. I hope my experience in processing my own deer helps you in your home butchering quest. I learned along the way, so I felt other people could too. Thanks for reading and happy processing.

Leave A Comment